Continuing Education

A Deeper Understanding of Pain

Learn more about how you understand and ultimately help clients who struggle with pain.

Pain is more than a physical experience. Learn how taking a more whole-person approach may help you help your clients better manage their pain.

by Troy Lavigne, August 1, 2025

Despite our natural inclination to shun pain, studies have consistently shown its inherent value as a protective mechanism. This innocuous four-letter word has the uncanny ability to disrupt our daily routines, and yet by delving into the mechanisms and behaviors associated with pain, we can actively adapt our perspectives and more effectively mitigate its impact on our lives.

Understanding someone’s pain can be difficult, and our understanding of their pain will never be as full as their experience. As massage therapists, we will never truly be correct in our conceptualization of our client’s pain experience.

Listening and gathering as much information as possible—alongside observation—is imperative. Our clients’ stories and language around their pain are key descriptive components and one of our only windows into understanding.

Pain has genetic, experiential and perceptual components that make how people experience pain highly variable between both individuals and cultures.1,2 Massage therapists must understand a client’s unique pain story and validate their experience to create client trust and open the doorway to communication.

Here, I hope to cover the multidimensional and contextual nature of pain, its evolutionary protective purpose, the role of suffering, and a more holistic approach to pain that includes brain training and community.

The International Association for the Study of Pain describes the phenomenon of pain this way: “An unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage.”

Other common components of pain include:

Although pain usually serves an adaptive role, it may have adverse effects on function and social and psychological well-being.

Verbal description is only one of several behaviors to express pain. Inability to communicate does not negate the possibility that a human or a nonhuman animal experiences pain.3

Learning the distinction between pain and nociception are valuable to our understanding of how pain has both positive and negative outcomes.4

Nociception refers to the central and peripheral nervous systems processing noxious stimuli and communicating potential damage (tissue damage, temperature increase, for example) to the brain via nerve fibers.

Pain, however, is the perception of said nociceptive stimuli and its individualized interpretation.

Traditionally, this means the nociceptive stimuli must surpass our allostatic load, which refers to the cumulative burden of chronic stress and life events.5 Once our allostatic load has been surpassed, our capacity to manage further input with a regulated response is no longer possible. This is frequently referred to as our “window of tolerance.”6

The brain controls threat perception and pain interpretation based on sensory inputs.7 When we’ve exceeded our own window of tolerance, the brain reacts to nociceptive stimuli with either a hyperarousal response or a hypoarousal response to said stimuli. The hyper or hypo response is the totality of the individual’s experience around the stimuli—through actual or imaginary stimuli—combined with reactive responses and predicted responses.

Both the perception and interpretation to stimuli are mandatory for the pain experience to exist.8 Perception or interpretation alone is insufficient for pain to be present. (Think of a bruise that you suddenly become aware of but can’t recall how you got it, for example. Once we are aware of the bruise and stimulate it, pain can be manifested. But, prior to the perception, the bruise was present with no pain symptoms.)

Interpretation, too, is just as essential. Imagine a tough workout, running a marathon or getting a tattoo. For some, any of these experiences might have painful elements, while others find strength or pleasure in the pain. How many times have you heard a client describe deep tissue massage as something that “hurts so good?”

Pain serves an important evolutionary function as an adaptive trait driving behavioral changes for self-protection and survival.9,10 Pain has also led to positive societal developments, like advancements in health care and technology.

Save by purchasing a Massage for Pain Relief CE bundle

The knee-jerk reaction to suppress pain with medication and/or treatment is normal, though possibly not always beneficial. Stepping away from our individual experience of pain and reflecting on its possible positive effects is often difficult, but may be a necessary component for a fuller, more holistic recovery.

Protection from Injury

Allowing the pain experience to be present and not suppressed acts as an alarm that helps trigger vigilance and protects us from behavior that could further induce injury and pain.11,12

Stepping away from our individual experience of pain and reflecting on its possible positive effects is often difficult, but may be a necessary component for a fuller, more holistic recovery.

Enhanced Sensory Input

Pain provides an essential contrast to pleasure so we’re able to enhance our sensory input, as well as increase our sensitivity to seek out pleasurable experiences. Pleasure and pain are frequently seen as oppositional, and though this idea may be somewhat accurate, pain and pleasure do not have a direct relationship.13,14,15,16 Being nauseous, for instance, doesn’t always denote pain, nor are painful workouts always seen as displeasurable.

Self-Regulation

Understanding that our experience of pain can frequently (though not always) be within our control has been shown to have analgesic effects similar to experimental pain study groups. Here, think about eating spicy food that induces sweating, tears, increased heart rate, and how that is a choice people make that is frequently seen as a challenge to strengthen themselves.

Pushing our limits of pain during training to further strengthen our tissue resistance or cardio system are seen as controlled interactions with pain rather than threat inducing interactions.17,18,19

Community Building

Sympathy, empathy and social support are often reactions to an expression of pain.20,21 Research tells us: “The ability to empathize, both in animals and humans, mediates prosocial behavior when sensitivity to others’ distress is paired with a drive toward their welfare.”22 Social support groups have been shown to encourage friendship bonding and help avert setbacks.23

In other words, pain is often unpleasant, but to solely focus on this single component of pain can limit our capacity to properly educate clients on their relationship to pain, how that relationship can assist them in recovery, as well as how they might lean into their relationship with pain to better manage outcomes.

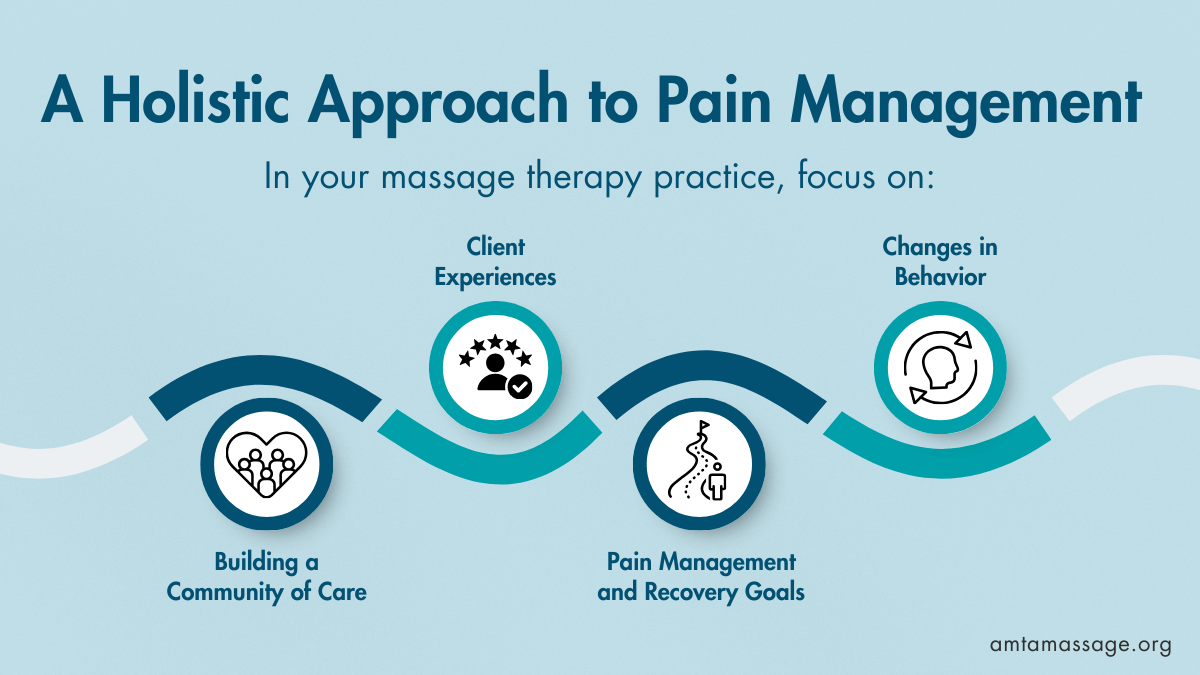

A holistic approach to pain management focuses on client experiences, pain management and recovery goals, changes in behavior and building a community of care24 rather than simply working on structural or biomechanical issues. (Though still valuable, structural and bio-mechanical cues for chronic pain are becoming less credible25 and taking a back seat to the contextual nature of painful experiences.26)

Linton et al. suggest several guiding principles that massage therapists may consider when working to incorporate a more integrative care and whole person approach to pain into their practice: